Werkbund

Experimental Werkbund Estates between 1927 and 1932

In 1927, the Weissenhof estate was built in Stuttgart as the first and most important proof of new and modern construction. The exhibition of the Deutscher Werkbund aimed to present new ways of eliminating post-WWI housing shortages and show new possibilities of practical and affordable housing construction. The call went out to 17 European modernist architects to design “housing for residents of a modern metropolis”. Today, the experimental buildings in the Weissenhof estate represent a unique manifestation of “classical” modernism and became an impetus for the Werkbunds in other European countries to create similar estates in Wrocław, Brno, Prague, Vienna, and Zurich. Although built with the same purpose and then divided by the distinct goings-on in post-WWII Europe, the estates found their way back to each other after the fall of the Iron Curtain, and they were awarded the European Heritage Label in March 2020.

Osada Baba – Praha

The President of the Czechoslovak Werkbund (the Czechoslovak counterpart of the German Werkbund), the architect Pavel Janák, designed several urban variations for the area of the future Baba estate on the outskirts of the city from 1928 onwards. In the end, it became a system of four parallel streets copying the contour lines with a checkerboard pattern of plots which provided privacy and a unique view of the city. This created private residential housing for the upper-middle class in detached houses, while excluding the social aspect and diverse building typology.

However, the attempt to build the last row of plots according to the designs from a student competition failed. Because of the economic crisis of 1933-1934, other ideas were suspended, such as a studio building, a sports pavilion, and a café pavilion.

In the years 1932-1936, a total of 33 buildings were built, 20 of which were implemented during the “Housing Exhibition” in autumn of 1932.

The Baba estate is a valuable example of interwar architecture, especially in terms of its sense of proportionality and urban and landscape design. Unlike other Werkbund estates, the houses were not built as “manifestations”, but their creation was based on a dialogue between the architects and the building owners (investors). This contributed to the Baba estate’s enormous influence on the spread of the ideas of functionalism in the field of housing, not only in Czechoslovakia but also internationally (Romania, Yugoslavia, Scandinavia).

All the houses have been preserved up to the present day and are privately owned. They have been listed as heritage sites since 1993.

Lainz Estate – Vienna

From its founding in 1912, the Austrian Werkbund focused on the availability of quality to a broader range of people. This aspect was also considered when constructing the Viennese Werkbund estate between 1930 and 1932; its motto was “Modern Types of Houses for Future Residential Estates – Economy Within the Smallest Possible Space”.

The Viennese site was created under the guidance of Josef Frank, who had already participated in the construction of the Weissenhof estate in Stuttgart in 1927. The 33 architects included one woman – Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky, three architects from other European countries – Gerrit Rietveld from the Netherlands, Hugo Häring from Germany, and André Lurcat from France – and Richard Neutra, a native of Vienna, who was already working in the USA at the time.

There was an exhibition in the summer of 1932 which lasted eight weeks and attracted more than 100,000 visitors, who were able to see 70 fully-furnished detached, semi-detached, triple, or terraced houses both from the outside and inside.

Between 2011 and 2017, all 48 houses owned by the city of Vienna were completely renovated. The purpose was to restore their original state while keeping in mind current housing standards. All the houses are now inhabited and therefore carry on in their original purpose.

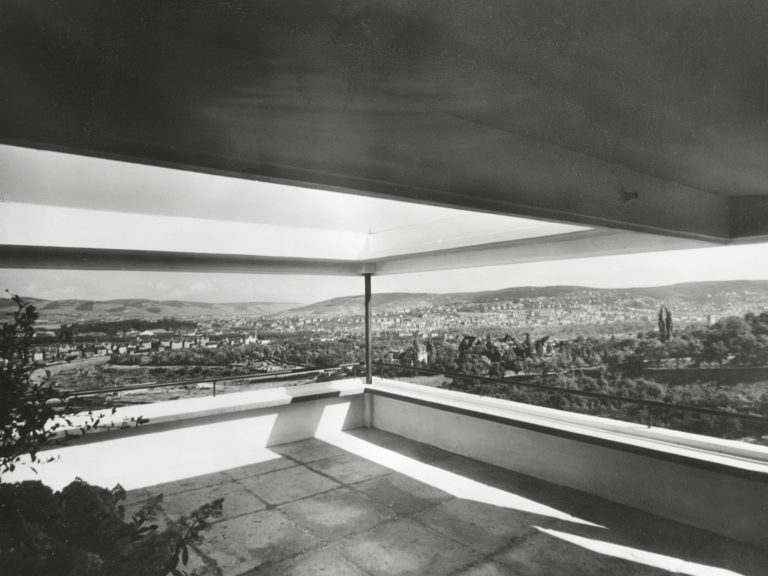

Neubühl Estate – Zurich

The Neubühl estate was also established as a Werkbund estate between 1927 and 1932; however, it was not awarded the European Heritage Label, as Switzerland is not an EU member.

This residential estate built between 1930 and 1932 is, like the other model locations, a testament to the modern construction of that time inspired by the Weissenhof estate in Stuttgart. The Swiss Werkbund initiated a working group formed in 1928 and the implementation was carried out by a newly-established non-profit cooperative.

The land, located on a hill ridge overlooking a lake, conformed to modern construction principles, as well as their requirements for sufficient fresh air and sunshine. The site encompasses various types of housing units – from one-room apartments to six-room houses. In addition, there is a common room, day nursery, shops, and studios.

With their flat roofs, bright façades and window strips, these cubic units correspond to the principles of the modernist movement in construction. The partition wall construction enabled an innovative layout of the floor plan and façade design that was independent of the structural system.

Unlike other Werkbund locations, the new construction method was not tested on other individually designed exhibition houses; in this case, the architects decided to conform to a higher principle. For this reason, it managed to become a comprehensive residential complex with various floor plans. In order to furnish the interiors, a separate company was established which manufactured furniture according to the architects’ designs.

From its development until today, the entire estate has been preserved as a whole; its overall design has been protected since 1978; it was listed as a cultural and historical heritage site in 1986, and since 2010, it has been protected as a heritage site.

WuWA Estate – Wrocław

Following the international reception of the Stuttgart exhibition of the Werkbund, Wrocław also came up with an exhibition, in 1929, entitled “Living and Work Space”. The aim was to present the latest forms of contemporary living and work spaces.

Over a period of three months, 32 buildings with 132 fully-furnished apartment units were open to visitors. The layout concept reflected the experimental and socially utopian ideas of the authors of the exhibition; it was their reaction to the social developments of the time (for example, how the role of women was changing in both the family and work environment). Therefore, the residential estate also housed a kindergarten, as well as a residence for single individuals by the architect Hans Scharoun and a high-rise building by Adolf Rading, all of which promoted new forms of cohabitation and living. After the exhibition was completed, the estate served for experimental purposes for two years and was inhabited mainly by artists, architects, and writers.

Over 80% of Wrocław was destroyed in WWII, but the WuWA estate remained virtually intact. The German Breslau became the Polish Wrocław, which was incorporated into Polish territory, and new residents found their new home here. The location was highly acclaimed among experts for its uniqueness. Since 1972, Scharoun’s residence for single individuals has been recognised as a heritage site, and since 1979, so have all the buildings of the WuWA residential estate. The urban area as a whole was recognised as a heritage site in 2007. The WuWA estate itself was included in the protection zone of the Centennial Hall located nearby, which was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2006.

New House Estate – Brno

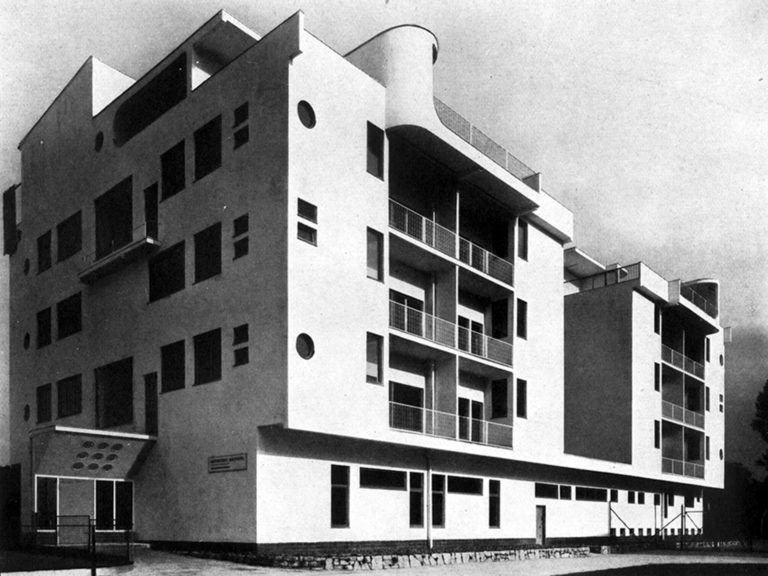

In 1928, the New House Estate exhibition was established in Brno-Žabovřesky as part of the “Exhibition of Contemporary Culture in Czechoslovakia”. Renowned architects supported by the Czechoslovak Werkbund designed 16 houses with a minimalist construction programme. The main objective was to create modern and affordable individual housing, primarily for young families.

The estate consisted of two detached houses, four semi-detached houses, and two terraced houses. All of the buildings had three to four floors, no basement, white façades, and a flat roof to serve as a roof terrace.

Similarly to the other Werkbund estates in other European countries, the Brno estate had difficulties in conveying the progressive ideas of the new architecture to a broader public. It was mainly the innovations to the interior layout that were met with a mixed reception.

After WWII, the socialist regime found a new purpose for the New House Estate.

Nowadays, the New House Estate is a testament to the efforts of the community of architects in Brno to keep up with the crucial development trends of modern European architecture, which shine through in many places in Brno, such as the world-famous Villa Tugendhat from 1930, designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (a present-day UNESCO site), as well as other houses in Brno’s Masaryk district or other important administrative buildings in the city centre.

Weissenhof Estate – Stuttgart

The Weissenhof estate was established in 1927 as part of the Deutscher Werkbund exhibition entitled “Apartment” (“Die Wohnung”). The objective of this experimental architectural exhibition was to present new ways of eliminating the post-WWI housing shortage and show practical and affordable forms of housing construction.

The call went out to 17 European avant-garde architects to design “housing for residents of a modern metropolis”. The speedy construction involved 21 fully functional experimental buildings with 63 apartments.

The Weissenhof estate represents a unique manifestation of “classical” modernism. There is no place like this where the erstwhile avant-garde was pronounced to such an extent as a collective programme. The consistent cubic form of the buildings stands as proof of the breakthrough of the new building style, which was later, in its form of “international style”, instrumental in the shaping of the 20th century.

During the era of National Socialism, the residential estate was described as a “cultural disgrace”, and ten houses were destroyed during WWII. Immediately after the war, the Weissenhof estate was somewhat neglected; however, it has been listed as a heritage site since 1958 and underwent a complete reconstruction in the 1980s. In 2006, the Weissenhof Museum was opened in a semi-detached house designed by Le Corbusier and, in 2016, both of his houses were listed as UNESCO World Heritage Sites as “The Architectural Work of Le Corbusier, an Outstanding Contribution to the Modern Movement”.